Let’s start with a real story of how not to choose participants for your emerging leader program. This pharmaceutical company had such a bad selection process that you can use it as a map of the mistakes you should avoid.

For context, this company has 1,000 sales reps and 100 sales managers. Here’s what the sales leader development team did:

For context, this company has 1,000 sales reps and 100 sales managers. Here’s what the sales leader development team did:

- They asked each sales manager to nominate one high-potential sales rep.

- They whittled those 100 selections down to 12 nominees.

- They hired an outside talent selection I/O psychologist.

- The psychologist designed a rigorous, four-month selection process.

- Candidates took personality assessments, went through interviews, completed assignments, and finished by preparing and presenting projects to a panel.

- Then, after all that, the leadership development team selected eight of those 12 sales reps.

- Four sales reps returned to their jobs, unable to participate (and probably pretty peeved).

Here’s the biggest problem with this approach: It’s too selective. This poor leadership development team spent a huge chunk of their budget to weed out and disengage 88 of their top performers. Then, they demanded a significant amount of time and energy from four of their absolute best sales reps (we’re talking top 1%), only to tell them that they weren’t quite good enough. Yikes.

Quantity: How Do You Decide How Many Emerging Leaders to Select?

I recommend that you think about this number in terms of two main categories of emerging leaders:

- Top talent to engage and retain. In the Pharma example, there’s a good chance that the eight leaders they chose went on to become great leaders. But, what about the 92 top sales reps they turned away? I cringe to think that they disengaged such a big portion of the top 10% of sales reps. Ideally, you want to engage and retain as large a percentage of that population as possible. Your emerging leader program is a great way to do so. Instead, this company poured hundreds of thousands of dollars into selecting and training only eight people. If retention is a key goal, expand your pool.

- Leaders to promote (replace manager attrition). Eight people does not cover this company’s average manager attrition rate of 20%. As managers leave or are promoted, about 20 seats will open up each year. At a bare minimum, you want 20 emerging leaders to choose from. Some will likely not be ready, and that’s okay because you don’t necessarily want all of your leaders to come up internally.

Generally speaking, both of the goals above point to the same solution: Broaden your pool. Even if many of your emerging leaders don’t siphon up into manager positions, development will help engage and retain them. In fact, emerging leadership development programs often help managers realize that they do not want to take a leadership role. And that is incredibly valuable.

Three Ways to Choose Your Participants

Here are three effective ways to consider handling your selection process:

- Have managers select, but don’t eliminate selections. Odds are, managers have a good grasp on who performs well and who would do well as a manager. Instead of weeding through their 100 selections to choose 12, take all 100 and develop them.

- Have employees self-select. If you want some checks and balances in place, you might ask your managers to confirm that those employees are a good fit for the emerging leader program and are at a good time in the year to handle the extra workload. But I’ve seen this work well with zero checks and balances.

- Select the top 10% or more of talent. Another way to select is to just take the top 10% of talent. No nominations, no weeding. Though, of course, there’s the whole debate about “what exactly makes a top 10% performer.”

All of these methods have something in common: They all seek to let more people in. Instead of spending your budget on selection, spend it on development. Imagine what the first pharma company could have done with all the money they spent weeding people out. They probably could have at least added the leaders they paid to eliminate (ironic!).

Regardless of your method, stay aware of how selection may interfere with diversity and equitable opportunity. Managers often carry biases. And, when team members know they weren’t selected by their manager, they can disengage. For these reasons, I tend to highly recommend self-selection.

Struggling to Choose One of the Above? Split Your Emerging Leader Program into Two Audiences

If you’re struggling to choose one of the above selection methods, it’s likely for the following reason (which I hear all the time):

“I want to have a big, equitable program that will develop anyone interested, but I also want a narrow ‘feeder’ program that pushes a select group of emerging leaders into management.”

There’s actually a simple, highly effective solution here: Split your audience. Do both.

At Ferring Pharmaceuticals, the Director of Commercial Leadership Development, Rob Daniel, did exactly this. He split emerging leaders into two main groups:

- Self-selected individual contributors: For the first program, Daniel allowed any sales rep to self-select. The program was six months long and focused on self-leadership topics like self-awareness, growth mindset, and emotional intelligence. This program helped Daniel’s team see who was interested in progressing and who was taking leadership development seriously.

- High-potential emerging leaders: This group of emerging leaders is already on track for a leadership position. They have a formalized individual development plan, have had serious conversations about becoming a leader, and have expressed a desire to lead people. This was a smaller audience (though still big enough to fill in for attrition). This program is a 12-month deep dive into leadership skills. It focuses on job shadowing and experiential learning. The goal of this program is to set emerging leaders up to thrive once they get promoted.

By building the program in this way, Daniel had his cake and ate it too. He engaged all talented sales reps while still getting selective as people progressed through the pipeline.

The number one objection to this style of program is price. But, Daniel actually ran both of these programs for less than the price of the failed emerging leader program at the beginning of this article. To do so, he leveraged self-driven learning, a behavior change platform, and group coaching. This made for a high-touch, expert-driven program that was still very cheap relative to the industry standard.

You can read more about Ferring’s approach here.

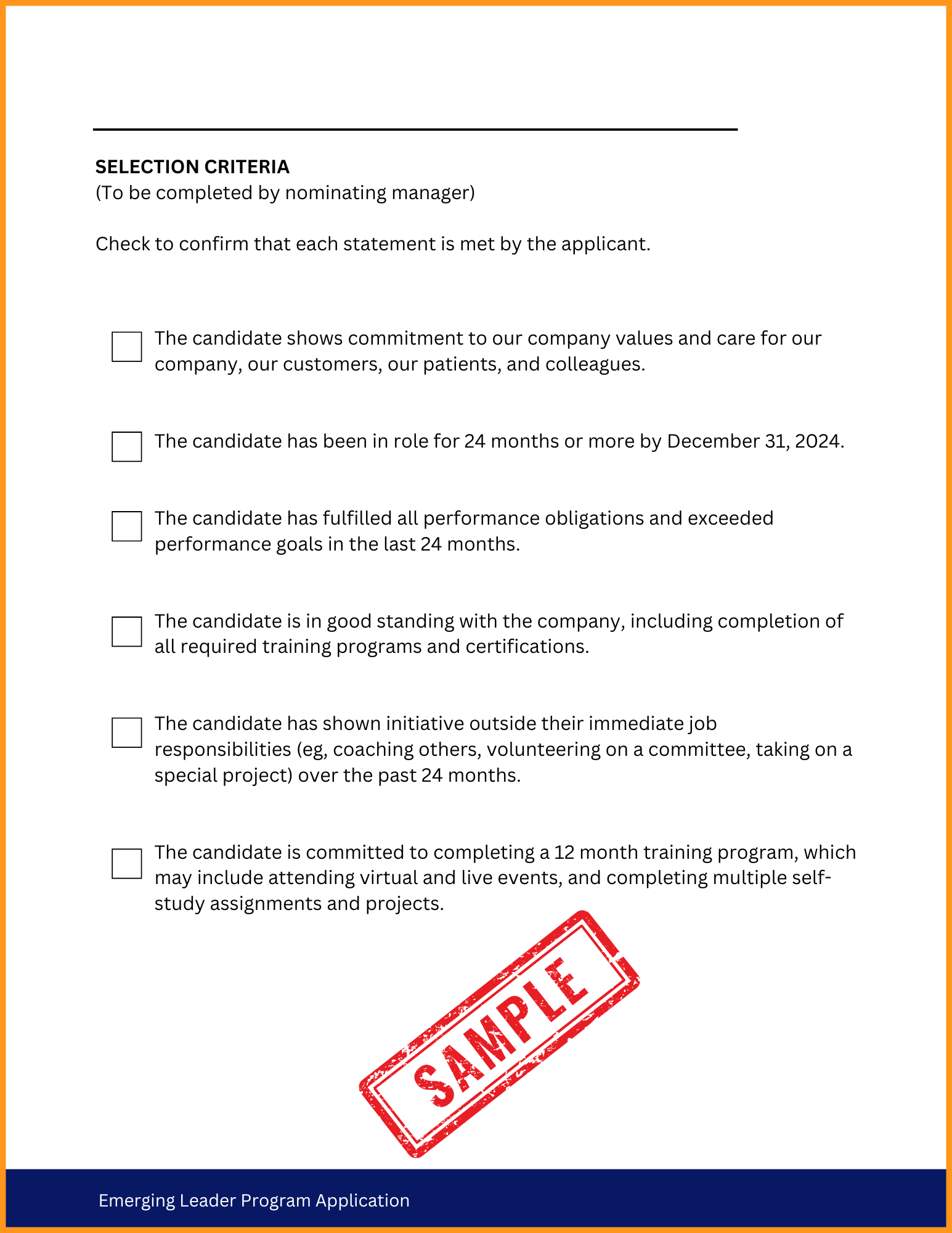

How to Evaluate and Select Your Candidates (If Not Self-Selected)

If you aren’t doing self-selection, then you need to determine your selection and evaluation criteria. Important things to consider include:

- Minimum tenure

- Minimum performance (and how to measure this)

- Essay questions (do you have them, and what are they?)

- Manager recommendation (beware of disengagement from those not selected)

- Live interview (how do you do this, and who conducts it?)

- Diversity (how do you ensure diversity and minimize bias?)

- Selection committee (who will be on it?)

Here’s a sample checklist:

At Olympus, for example, their emerging leader program used a selection committee to choose 20 participants from 40 applicants. With 80 first-line leaders across the organization, the target audience size would easily fill in for attrition. Olympus’s application process included a variety of criteria, such as:

- Modeling Olympus values.

- High performance: Set by each business unit, based on the 9-box model.

- DE&I.

- Diversity in geography.

- Sales results.

- Achievements (e.g., field trainer responsibilities, national impact, and elite/quota performance).

- A letter of recommendation from your manager. A panel then reviewed and rated each essay.

- An essay assignment based on leadership competencies.

- A panel interview of each candidate’s manager.

For an in-depth look at a more intensive selection process, check out how Olympus does it here.

Promote Your Program Internally: A Story-Based Approach

Regardless of how big or small your audience is, you need to promote your program. If it’s open enrollment, you want to draw as many people as possible. And if it’s application-based, you want it to be as competitive as possible. Here are five guideposts to market your program.

- Make your audience the “hero” of your messaging. Show them what they have to gain by going through your program. Don’t get caught up in all the details, topics, and assessments that you personally geek out on. Focus on emerging leader success stories.

- Bring up the challenges your emerging leaders will face and how your program will help them rise above those challenges. For example, you might point out how tough it can be to transition from being great at sales to being great at leading a sales team, or how it can be difficult to know whether or not you want to lead people.

- Present your program as the answer to their challenge. Show how your program will help solve their challenge and guide them through it. Now is when you can geek out a bit and talk about how different topics and activities will help them overcome those challenges. For example, “By shadowing our best current manager, you will see first-hand what it takes to succeed as a manager.”

- Show your audience what they might lose by not joining your program. For example, you might point out that they may never know whether they want to take on a leadership role. Or, they may never be considered for the role.

- Be clear and concise. Make it easy for people to understand what they have to gain from your program.

Be sure to include testimonials if your program is already up and running. A great testimonial from an alumni may even touch on all of the above points.

Putting It All Together: When In Doubt, Expand Your Pool

Selection is daunting. But it’s worth being intentional about your process. Your audience is your program. My sweeping advice: If you’re unsure, expand your pool. You’ll regret passing up a potentially great leader more than you’ll regret developing a high-performer who never progresses into a leadership position.