What’s one specific way to manage up?

It’s 4:45 p.m., you get an email notification and your chest tightens. It’s the boss, and while you’re sure you didn’t do anything wrong, you still feel anxious about what’s in the contents. She’s asking for the status on multiple projects, or maybe reminding you about tasks that you’re already close to completing. Is there a way for an employee to change the dynamic of this professional relationship and save themselves some stress?

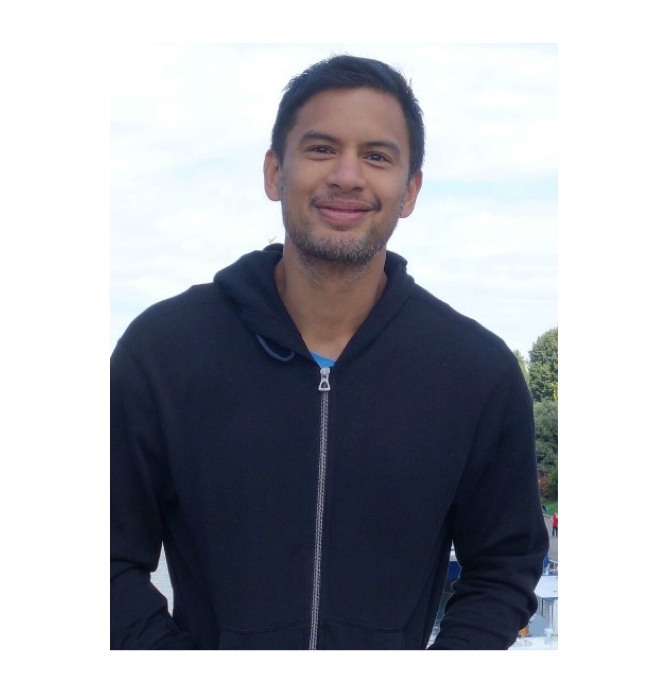

Khe Hy has spent 15 years in the financial services industry researching hedge fund investments. He was a managing director at Black Rock when he left in 2015 to explore projects focused on introspection, generosity and community. Today he's an entrepreneur in residence at Quartz and he's the founder of the media company Rad Reads, which has a newsletter with over 15,000 subscribers and it's comprised of leaders, investors, academics, and change makers. I read his article, The 15-minute Weekly Habit That Eased My Work Anxiety, published on Quartz, and had to interview him for the LEADx Podcast, where we discussed his approach to work, life, and emails. (The interview below has been lightly edited for space and clarity.)

Kevin Kruse: In your article, you mention a boss emailing you the words “Call me,” often, and how that triggered anxiety. Explain the habit that improved that relationship.

Khe Hy: I’ve always been very afraid. I think maybe it's cultural. Maybe it's because as a teenager I was kind of shy and insecure and never really felt socially accepted. That's a different conversation. I guess–and I've worked in these intense industries–so my default reaction was always, “Shoot. I did something wrong.”

There was a huge cognitive dissonance because I'm very hard-working. I'm very thorough. People look up to me at my job. I was asking myself, “Why is there this disconnect and what can I do to avoid it?” Really, I thought of it as an insurance policy, or even more, I thought of it as a game. The game was if someone senior to me ever has to ask me, “Hey, where's that thing? Where's that Powerpoint? Did you send that email? Did you check in with that person?” If they ever had to ask me that question, I have done a bad job at managing their expectations. If you pair that with empathy, where you kind of understand the rhythm that people work at, or their cadence, when you put those two together, you can kind of anticipate.

You have the one boss that asks you something and then checks in three days later. Just make sure that by day 2.9, you've finished the task. You can't always get it to be that granular, but what I figured was, “Why don't I just send this email where I say what I'm working on, what's open-ended, what's completed, and send it off?” Give myself 10 to 15 minutes to do it. That way, it pretty much covered that he'll never call and ask me, “Hey, where is that thing?”, because he will know the answer. I did it as an insurance policy knowing myself, knowing that I get triggered by a lot of that fear and saying, “I don't want that anymore.” That was kind of a catch-all way to do it.

Kruse: As you start to understand kind of the rhythm and the moods of your manager, that helps you also to communicate proactively.

Hy: Absolutely. There were some tangential side benefits; it was an excuse to humble brag. You did the task. You're not bragging. It's a fact. You're kind of always staying top of mind in your manager in the way you want to be remembered. On top of that, you're doing the manager a favor because–in this case it was a he–he knows that you're on top of things, so he doesn't need to worry about the things that he hands off to you. He has to commit his mind space to another direct report. I would set timers, because if it ever takes more than 15 minutes, it might not be worth it. Kevin, I tell you, I'm 38 years old, I'm Entrepreneur in Residence at Quartz, which is not even anything close to a full-time job. I still, to this day, send that email to the founder of Quartz every Friday.

Kruse: It's such a powerful and simple tool, because it allows you remind supervisors and even clients that you haven’t forgotten anything.

Hy: What I would add is that when you don't have that communication, then people's imaginations start to run wild. By doing that I was preventing someone's imagination from running wild because it's like, “These are where these things are.” Game over. Not like, “Is he waiting until the last minute to do this? Did he forget?” The reality, even if I didn't send the email, was none of those things were true, but by not sending it, then my boss' head could go to all these places. Then he would take it back on me. Then it's like everyone loses.

Kruse: I always like to challenge our listeners to get 1% better every day. What would you challenge us to do today? 15-minute email?

Hy: I'm still blown away. I've met so many professionals in my life, and I could count on two hands the number of people that do it. I don't know why people don't do it. I'll give you something more original. I think, and this is going to be a little contrarian, or maybe a little different, but the one challenge that I would give your listeners is try to make someone else better every day. That can be really simple like sending them an article on something you think that they're thinking about. It could be making an introduction. I like to call them MBI's, which are ‘Mutually Beneficial Introductions,’ where [for example] two friends of yours are really into Bitcoin. Just connect them. See what happens. Obviously with a double opt-in. Always check.

Something that I really believe in, which I call “do free work”, which is just someone's working on a proposal or a manuscript or a blog post. Offer to read it and give them some quick comments. I think that by doing that, helping someone releases oxytocin in your brain so it will actually physically make you feel better. But you will build up this groundswell of amazing relationships and friends and people who will have your back, and you will learn about the things that matter to them.

Kruse: What advice would you give yourself when you were starting out in your 20s?

Hy: This is actually a perfect transition, because it's the thing that I didn't do in my entire twenties. I never ever looked within myself. I never looked at my fears. I never looked at my insecurities. I just went work, work, work, work, hustle, connect, read, don't sleep. The way that I think about it is what I did was–imagine if I said to you, “Kevin, hey, I'm 21 years old and I'm not going to start going to the gym until I become a managing director at a financial services firm because I need to dedicate every single minute to getting that title.”

I basically did that for myself emotionally. I think that many professionals, more so males, are motivated by–it's not like skeletons in your closet, but it's just kind of normal human angst. Why does an email that says “Call me,” trigger your fight or flight reflex? We're biologically wired that way. On top of that, we might have been picked on when we were 12 years old, or we might not have had the relationship with our parents that we wanted, or we might have been huge nerds that were ostracized in high school. What I learned about myself was I'd built up all these tactics to combat that, almost thinking that I could outrun some of these feelings, thinking that more status, more money, more titles would make those feelings go away. Boy, was I wrong. It took me 15 years to figure that out.

If I had done those things, I argue I would have been more successful. We know that with fitness. That's kind of accepted now culturally, that a healthy body makes for a healthy mind. I would say a healthy mind makes for killer instinct in business if that's what you're seeking, which I would imagine many people are, many of your listeners are.

Kruse: What's your advice to first-time managers?

Hy: I would say that the best piece of advice would be to, and I would explicitly say this, is care about your direct reports as if they were family members. The example that I give is you often see a high performer, direct reports, raises their hand and says, “I want to go to business school.” Then the boss might say, “Oh my God, I can't lose this high performer. There'll be a huge hole in the coverage. Who will replace him or her?” I think that is the worst way to think about it as a manager, because I think humanity over corporations. I think that's just a grounding ethical principle of mine.

Again to that point about these kinds of second order effects, these unintended positive consequences, you have the reputation of the person who cares about the employee first. Guess what? Everyone wants to work for you. Younger people will try to raise their hands to move into your group. Guess what? You leave on good terms with that person who goes to get their MBA. They end up at a firm. Now they're a client. “Thank you for being so supportive of me. Can we give you business?” Even better, you're looking for a job. Needless to say, we spend 60-70% of our waking hours, we spend more time with our colleagues than we do with our spouses. Of course, you should care that way. I guess A) it's the right thing to do, B) the positive unintended consequences will be huge, and C) it's just the right way. Again, it's the humanity of really building meaningful relationships.

—

Kevin Kruse is a New York Times bestselling author, host of the popular LEADx Leadership Podcast, and the CEO/Founder of LEADx.org, which provides free world-class leadership training, professional development and career advice for anyone, anywhere.